[title type="h5"]Sunday, March 15, 2015.

Chefs Soiree. A Major Passing.[/title]

The time change (did it become matter? or a slightly different new dimension?) shifts our lives a little. The newspaper took a poll as to whether people prefer the clock alteration, and we learn that many folks don't like the later sunset. Next to that is an article about how the throw of that switch messes up human circadian rhythms. Given how easy it is to sleep late when I get to bed late, I find this hard to credit. I'd like to see a poll that investigates what percentage of people don't like anything.

People in the restaurant business decidedly dislike DST. For most restaurant patrons (exceptions: children and the elderly), dining out is something you do after dark. During DST, by the time it's dark enough for people to head out to dinner, it's late enough that they either cancel the reservation or go to a restaurant on the lighter, simpler side. Nor do they drink as much.

[title type="h5"]Sunday, March 15, 2015.

Chefs Soiree. A Major Passing.[/title]

The time change (did it become matter? or a slightly different new dimension?) shifts our lives a little. The newspaper took a poll as to whether people prefer the clock alteration, and we learn that many folks don't like the later sunset. Next to that is an article about how the throw of that switch messes up human circadian rhythms. Given how easy it is to sleep late when I get to bed late, I find this hard to credit. I'd like to see a poll that investigates what percentage of people don't like anything.

People in the restaurant business decidedly dislike DST. For most restaurant patrons (exceptions: children and the elderly), dining out is something you do after dark. During DST, by the time it's dark enough for people to head out to dinner, it's late enough that they either cancel the reservation or go to a restaurant on the lighter, simpler side. Nor do they drink as much.

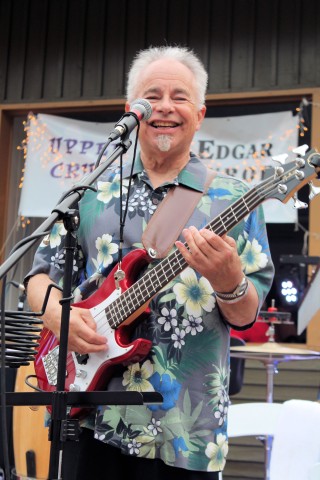

[caption id="attachment_46986" align="alignright" width="320"]

[caption id="attachment_46986" align="alignright" width="320"] Benny Grunch at Chefs' Soiree.[/caption]The Marys, niece Hillary, and I go to the Chef's Soiree at the Bogue Falaya State Park in Covington. It's the best running of this 31-year event that we can remember. The weather is perfect. Delectable food comes from every booth. All the longtime chefs are here. Pat Gallagher has his usual kebabs of steak and squash and shrimp bisque--and the longest lines. But many other restaurants are near his level of goodness. Best new addition: Isabella's Pizza, which for a long time was mediocre but now is baking its pie in wood-fired ovens, to excellent effect. Benny Grunch and the Bunch play for most of the four hours. The wines are much better than in past years, and it was even possible to get a reasonably good cocktail.

The Chef Soiree raffles off a new car every year. I don't know why I buy a hundred dollars' worth of tickets each time, because otherwise I am not a gambler. This year, my investment is especially absurd. As Mary Leigh points out, a black, swept-back Mustang fits my personality about as much as a mohawk haircut would. I am saved from that dilemma when none of my five tickets score anything.

When we get home, I find in my e-mailbox a note from Eat Club regular and Tableau bartender Lisa Schelhaas. It says that Mr. Dick Brennan died yesterday evening. The newspaper confirms this. He was eighty-three. The cause of death, I would later learn, is a kidney problem.

But I don't need many details to get to work on my appreciation of Dick Brennan. Early in my career, he persuaded me that if I wanted to make a living writing about food, I had to do a much better job of it. Coming from Dick, that was a command from on high. He and his brothers and sisters created Brennan's and all the other restaurants the family opened afterwards. Together, those restaurants revolutionized New Orleans dining for decades.

Although I have other articles on deadline, I am compelled to give this one all my attention. I spend five hours writing its five pages. It is very personal. Dick was not just a mentor, but a father figure for me. And for many other people, including some of the most famous local chefs and restaurateurs. (No need to write it all over again now; the article is permanently here.) [divider type=""]

[title type="h5"]Monday, March 16, 2015.

We Are Sprung. A Powerful Force.[/title]

The heavy rains that left large puddles around the property last week have mostly drained out, even though I have to re-route my semi-daily walkabout to avoid the squishy spots. It's times like this that make me realize that, even at thirty-eight feet above sea level, we live in wetlands.

I take longer than usual for my walk. I mull over the idea that Dick Brennan is gone. His passing ends an era for me and a lot of other people. It is hard to credit the idea that people my age must now fill the shoes of Dick and his generation. Things like this enter my mind: when Dick thought it was time to read me my beads, he was fifteen years younger than I am now.

Between such thoughts, I take in some less troubling ones. Everything in the woods is sprouting, all at the same time. The grotto-like clearing along the trail is about a quarter full with its blanket of ferns. I hear the morning calls of several randy birds. The four cypress trees I planted twenty-five years ago are pushing out their needles. The star-like sweetgum leaves are unfolding. And this is the week when tall pine trees cast off cones. One of them almost hits me in the head as it hurtles down at great speed. None of those developments had even begun a week ago. And Dick Brennan was still with us.

The Marys go to La Caretta without informing me. I make a ham sandwich for my only meal of the day. I go to choral rehearsal. One thing I've noticed about singing in many choirs (all of them amateur) over the years is that the leader will never single out a person to tell him that he's off key or having some other problem. The leader instead backs up to the mistake and runs it again, as if it were the whole group that had goofed up. The first such for me was in seventh grade, by which time I had already been singing for three years. The nun who led the chorus came up behind me, lowered her head to listen closely, and told me to leave the room because I had a cold. I did not have a cold. It would be many years before I sang in public again. Eleven-year-olds are sensitive.

Tonight, the leader of my current chorus pointed at me, said my name, and told me I had just unloosed a foul A-flat on an unsuspecting world. I'm sure I had. I would hit the A the next time through, that's all. She's a terrific conductor and in just a few months I have learned a great deal about singing, which is what I am there for.

But Dick Brennan is on my mind tonight.

Benny Grunch at Chefs' Soiree.[/caption]The Marys, niece Hillary, and I go to the Chef's Soiree at the Bogue Falaya State Park in Covington. It's the best running of this 31-year event that we can remember. The weather is perfect. Delectable food comes from every booth. All the longtime chefs are here. Pat Gallagher has his usual kebabs of steak and squash and shrimp bisque--and the longest lines. But many other restaurants are near his level of goodness. Best new addition: Isabella's Pizza, which for a long time was mediocre but now is baking its pie in wood-fired ovens, to excellent effect. Benny Grunch and the Bunch play for most of the four hours. The wines are much better than in past years, and it was even possible to get a reasonably good cocktail.

The Chef Soiree raffles off a new car every year. I don't know why I buy a hundred dollars' worth of tickets each time, because otherwise I am not a gambler. This year, my investment is especially absurd. As Mary Leigh points out, a black, swept-back Mustang fits my personality about as much as a mohawk haircut would. I am saved from that dilemma when none of my five tickets score anything.

When we get home, I find in my e-mailbox a note from Eat Club regular and Tableau bartender Lisa Schelhaas. It says that Mr. Dick Brennan died yesterday evening. The newspaper confirms this. He was eighty-three. The cause of death, I would later learn, is a kidney problem.

But I don't need many details to get to work on my appreciation of Dick Brennan. Early in my career, he persuaded me that if I wanted to make a living writing about food, I had to do a much better job of it. Coming from Dick, that was a command from on high. He and his brothers and sisters created Brennan's and all the other restaurants the family opened afterwards. Together, those restaurants revolutionized New Orleans dining for decades.

Although I have other articles on deadline, I am compelled to give this one all my attention. I spend five hours writing its five pages. It is very personal. Dick was not just a mentor, but a father figure for me. And for many other people, including some of the most famous local chefs and restaurateurs. (No need to write it all over again now; the article is permanently here.) [divider type=""]

[title type="h5"]Monday, March 16, 2015.

We Are Sprung. A Powerful Force.[/title]

The heavy rains that left large puddles around the property last week have mostly drained out, even though I have to re-route my semi-daily walkabout to avoid the squishy spots. It's times like this that make me realize that, even at thirty-eight feet above sea level, we live in wetlands.

I take longer than usual for my walk. I mull over the idea that Dick Brennan is gone. His passing ends an era for me and a lot of other people. It is hard to credit the idea that people my age must now fill the shoes of Dick and his generation. Things like this enter my mind: when Dick thought it was time to read me my beads, he was fifteen years younger than I am now.

Between such thoughts, I take in some less troubling ones. Everything in the woods is sprouting, all at the same time. The grotto-like clearing along the trail is about a quarter full with its blanket of ferns. I hear the morning calls of several randy birds. The four cypress trees I planted twenty-five years ago are pushing out their needles. The star-like sweetgum leaves are unfolding. And this is the week when tall pine trees cast off cones. One of them almost hits me in the head as it hurtles down at great speed. None of those developments had even begun a week ago. And Dick Brennan was still with us.

The Marys go to La Caretta without informing me. I make a ham sandwich for my only meal of the day. I go to choral rehearsal. One thing I've noticed about singing in many choirs (all of them amateur) over the years is that the leader will never single out a person to tell him that he's off key or having some other problem. The leader instead backs up to the mistake and runs it again, as if it were the whole group that had goofed up. The first such for me was in seventh grade, by which time I had already been singing for three years. The nun who led the chorus came up behind me, lowered her head to listen closely, and told me to leave the room because I had a cold. I did not have a cold. It would be many years before I sang in public again. Eleven-year-olds are sensitive.

Tonight, the leader of my current chorus pointed at me, said my name, and told me I had just unloosed a foul A-flat on an unsuspecting world. I'm sure I had. I would hit the A the next time through, that's all. She's a terrific conductor and in just a few months I have learned a great deal about singing, which is what I am there for.

But Dick Brennan is on my mind tonight.

Written by Tom Fitzmorris March 24, 2015 12:01 in